In my most recent post I looked at a

proposal by Newton mayor Wayne Levante to create a single, countywide district for Sussex County.

Although such a consolidation would be politically difficult and perhaps only reduce Sussex County's taxes by 1%, I realized that consolidating Sussex was a sound idea, since Sussex County's taxes are extremely high, its school districts are very small, and several of Sussex's small districts will not be able to accommodate further enrollment loss and/or loss of Adjustment Aid as stand-alone entities.

Aside from a sentimental (but strong) attachment to home rule, the primary difficulty of consolidation would be evening out unequal school taxes and spending, but Sussex's tax and spending differences are narrower than in most other counties, so Mayor Levante's "uphill fight" for Sussex consolidation is less steep than it should be for other counties.

In this post I turn my attention to proposals by Paul Tractenberg to create a consolidated Essex County district and how such a design would be infinitely more difficult to implement and operate than a consolidated Sussex County district would.

Tractenberg has advocated for an Essex County consolidated district several times. Here's an

extended argument for an Essex superdistrict from 2013:

The use of Essex County as a pilot for the county school district model requires elaboration. By the usual New Jersey political calculus, it is a solution with no chance of being tried. It runs afoul of some formidable political bosses and some very wealthy and influential suburban residents. It runs head-on into the glib and dismissive badmouthing of cities like Newark, Irvington, East Orange, and Orange. If there was ever a quintessential political third rail, this seems like it.

Yet Essex County, although it is quite populous, is one of New Jersey�s smallest and most compact counties. You can drive from one end of it to the other in not much more than 30 minutes. In other times, Verona actually implemented a voluntary program under which students came from Newark to attend the Verona schools and that was not seen as logistically or politically infeasible.

NJ's Most Segregated County

Essex County is also by far the state�s most segregated county. Its 21 school districts include four that are urban, desperately poor, and almost entirely populated by students of color; five that are relatively diverse, two (Montclair and South Orange-Maplewood) by conscious choice; and 12 that are overwhelmingly white and higher-income with virtually not a single low-income student.

These extraordinary disparities, and frightening isolation and separation, literally exist side by side. If ever there seemed to be a situation that met the New Jersey Supreme Court�s constitutional standard -- that schools have to be racially balanced �wherever feasible� -- Essex County seems to be it. And if Brown v. Board of Education and its implementation in the South established anything, as a matter of law, it was that politically and racially inspired opposition to a constitutional command could not succeed.

Now it�s time for us to decide. Do we stay with the status quo of two separate and unequal state systems of education, or, if we don�t, do we embrace a �radical� reform approach based on constitutional imperatives and the best available evidence or one that defies the constitution and the evidence?

Before I outline the huge difficulties of consolidation, I want to say that I live in an integrated suburb (South Orange) and agree that integration benefits poor, minority students academically. The inequalities of taxation in Essex are also brutal and and do much to stifle revival in Newark, Orange, East Orange, and Irvington. Because tax rates are so bad in urban Essex

I've called for a countywide school tax to be distributed between independent districts.

However, the bottom line of Essex consolidation is that the same inequality makes consolidation all the more educationally necessary makes consolidation all the more fiscally difficult.

Whereas in Sussex, consolidation is feasible within the existing budget and might even save money on administration, in Essex,

consolidation would require massive infusions of municipal aid for the urban towns and probably quite a lot of additional money for bussing.Also, were the tax benefits of consolidation solely to the poor, and its tax costs were solely borne by the rich, at least it would be a unambiguous goal for progressives to fight for, but in actuality the costs of consolidation would primarily be born by the four Abbotts, not the rich suburbs.

Even the tax problem were solved and consolidation were implemented, the countywide district's schools would be segregated due to housing patterns. It would be necessary to use bussing to solve school segregation, which is itself an expense greater than any savings through needing fewer administrators. If the bussing were mandatory it would incense large segments of the population.

Even if the tax problems were solved and any bussing were voluntary, there is a lack of space in all the large suburban districts in Essex. Unless residential students in suburban Essex were induced to attend school in urban Essex, there would not be enough space to accommodate more than a relative handful children currently attending school in Orange, Irvington, East Orange, and Newark.

Tractenberg's Proposal Would Make the Poor Pay MoreThe first challenge in devising a countywide district is how taxes would be apportioned and on this issue consolidation slams into the rocks.

Let's assume that an Essex County superdistrict would apportion taxes based on Equalized Valuation, like county government already does.

Essex County's (weighted) average school tax rate is 1.3, based on $1.099 billion in total school taxes on $84.8 billion in Equalized Valuation, but that rate varies and the pattern of school taxation is n-shaped, where

rich towns and the Abbotts tax the least and middle class towns tax the most.

Thus, a move that would create a common, flat tax rate, like a consolidated district would require, would make the rich and the Abbotts to pay more.

|

Sourece:

http://www.state.nj.us/dca/divisions/dlgs/resources/property_tax.html#1 |

East Orange actually has the lowest school taxes in Essex, at a rate that is only 0.797. The other Essex County Abbotts, Orange (0.818), Newark (0.9), Irvington (0.943), have low taxes as well.

A few of Essex County's rich towns, like Essex Fells (0.923), Roseland (0.963), and Millburn (0.853) also have low tax rates and so would pay more in taxes, but their combined increases are less than the increase for Newark alone.

How high would taxes go?

For instance, Newark now pays 12% of Essex County's school taxes ($130 million out of $1.099 billion), but Newark has 16.2% of Essex County's Equalized Valuation, so if an Essex County superdistrict were formed and the tax levy stayed the same and converged on that 1.3 average,

Newark's 16.2% of school taxes would become $178 million. |

Source, http://www.state.nj.us/dca/divisions/dlgs/resources/property_tax.html#1

Own calculation, based on a town's share of Essex County's total Equalized Valuation and $1.099 existing tax levy. |

East Orange would also see a large increase. East Orange has 3.2% of Essex County's total Equalized Valuation ($2.7 billion out of $84.9 billion). If East Orange paid 3.2% of Essex County's school taxes its bill would be $35.1 million, a dramatically higher figure than the $21 million figure it pays now.

Orange would pay another $7 million, Irvington would pay another $7.2 million.

Millburn has 11.5% of Essex's total Equalized Valuation. In an Essex County superdistrict Millburn's taxes would have to be 11.5% of $1.099 billion, or $102.5, a $20 million increase on the $83 million Millburn pays now. Roseland would pay another $6.1 million, North Caldwell would pay another $2 million. Fairfield would pay another $10 million.

The biggest tax beneficiaries of Essex consolidation would be working class and middle-income non-Abbotts of Essex County who lack the tax bases to have low taxes, but receive so little state aid that they have no choice but to be high taxers. South Orange-Maplewood, West Orange, Glen Ridge, Verona, Bloomfield, and Belleville could look forward to lower taxes. Glen Ridge, Belleville, Bloomfield, and Verona would probably spend more too. Verona might get the full-day kindergarten that it currently lacks.

Montclair's taxes would theoretically fall by $25 million. Bloomfield's would fall by $16.9 million. South Orange-Maplewood's would fall by $30.3 million.

West Orange's taxes would fall the most.

West Orange's taxes would fall from $132 million to only $62 million!

West Orange, however, is a high spending district, with a Total Budgetary Cost Per Pupil of $18,277. It's likely West Orange's schools would have to make cuts if a countywide district came into being, so not everyone in West Orange would be happy about the other implications of consolidation.

The need for certain districts to make cuts exacerbates the political impossibility of a countywide district. Home rule has is benefits and one of them is that districts can decide for themselves how much to tax and spend.

Disparities in Municipal Taxation Exacerbate ChallengesWhat heightens the challenge of equalizing Essex County's school tax rate is that municipal taxes are extremely high in the Abbotts (due in part to decades of massive school aid offsetting their school taxes). Unless there were some tremendous infusion of municipal aid for the Abbotts and/or cost cutting there, the differences in municipal taxes also make consolidation deeply unpopular even in the urban districts that Tractenberg believes would benefit.

|

Source:

http://www.state.nj.us/dca/divisions/dlgs/resources/property_tax.html#1 |

Cedar Grove, Essex Fells, Livingston, Millburn, and North Caldwell have muni tax rates below 0.5, with the other suburbs having gradually larger tax rates.

Newark's muni tax rate is 1.642, but Orange's tax rate is 2.872, East Orange's is 3.353, and Irvington's is the highest in New Jersey, at 3.475. Belleville's municipal tax rate is very high too, at 1.836, although nothing compared to East Orange and Irvington.

Essex County's inequalities of municipal taxation are actually the worst in New Jersey, as measured by the standard deviation of the tax rates.

If Newark, had to pay a 1.3 school tax rate, on top of its 1.642 muni tax rate and the existing county government tax of 0.5, it would have a 3.3 tax rate. Orange's tax rate would rise to 4.7, East Orange's would rise to 5.1, and Irvington's would rise to 5.2.

If school taxes are somehow conditioned on municipal taxes so that towns with higher muni taxes paid less, it would mean higher school taxes for Essex's wealthy towns and probably its middle class towns too. Making school taxes conditioned on municipal taxes would also incentivize municipal bloat, since higher municipal taxes would mean lower school taxes.

Although the main reason the urban towns have high muni taxes is greater need, there is also waste. In urban New Jersey, municipal spending is a jobs program as much as public service. (

example 1,

example 2)

Although I would expect Orange, Irvington, East Orange to have high muni taxes given their poverty and support robust municipal aid for them, there is little justification for their municipal tax rates to be

double what Belleville's is. When poor non-Abbotts like East Newark (1.4), Fairview (1.1), Dover (1.1), Prospect Park (1.5) have much, much lower municipal taxes, I suspect that the huge infusion of state aid allowed municipal taxes to spike sky-high since school taxes were frozen.

What About Abbott PreK and 100% Construction Funding?A further inequality of Essex that doesn't exist in Sussex is that Essex County has its four Abbott districts and these districts thus get the state to pay for 100% of their construction costs and pay for universal PreK for 3s and 4s (PreK in the four Abbotts costs NJ a combined total of $136 million)

If Essex County were consolidated into a single district, it's hard to imagine how these privileges would continue just for Newark, Orange, East Orange, and Irvington. Kids who live in the same jurisdiction would have to be treated equally and the new district and the state and new superdistrict are unlikely to have the money to fund that.

I estimate that Belleville alone has 650 children who are three or four years old. If all of those children were to get "free" PreK it would cost $8.1 million. Even if PreK were restricted to Free & Reduced Lunch eligible children in the hitherto non-Abbotts it would cost tens of millions countywide.

Tractenberg's new Essex County superdistrict would also have a disparity to settle regarding construction funding, since right now the Abbotts don't pay for any of that.

So, a fix for construction funding would have to be yet another issue settled before an Essex superdistrict could be created.

What About Per Pupil Tax Apportionment?A tax scenario that would be even more difficult for poor towns would be to apportion taxes based on how many students come from a town.

I don't think any objective observer would want taxes to be apportioned by student population, but as a political compromise it might be necessary to get affluent towns to go along with a consolidation proposal.

If, hypothetically, taxes were apportioned by student population, and Newark ended up paying 38% of taxes because it has 38% of the student population, Newark's taxes would be $338 million, an impossible amount for Newark that would require a 2.5% school tax rate.

(See note at bottom on apportioning taxes by Local Fair Share)

Suburban School Districts Don't Have Room Another practical problem with consolidation is if Tractenberg's goal is for urban students to be able to attend suburban schools, there is no room for them without new schools being built.

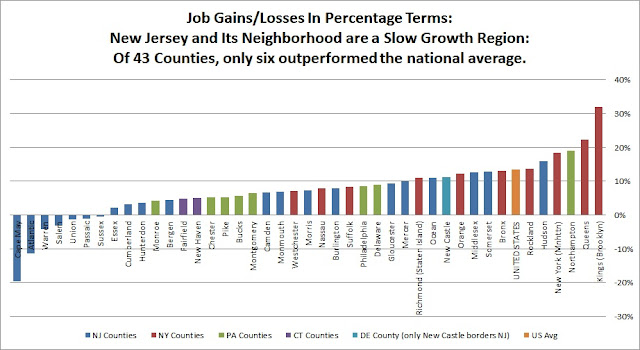

In the last ten years, almost all of suburban Essex districts have seen student population increases, topping out with 14% increases in South Orange-Maplewood and Bloomfield.

Although Montclair's increase has been modest since 2006-07, that 1% increase on top of existing crowding was enough to

persuade Montclair's superintendent to not participate in Interdistrict Choice, despite the huge state money infusion it would have provided and despite the fact that Montclair had recently opened a new school.

'The issue for us is limited school space, even with the new Bullock School,' [Superintendent] Alvarez explained. 'We don't have excess capacity, and the capacity we do have can be utilized better by bringing our district's special needs students back to Montclair.'

Paul Tractenberg praises Verona for accepting a few dozen Newark students for one year a generation ago,

but that was in 1969, a moment when Verona's student population had fallen significantly and classrooms had empty seats.

Essex County is the only county in New Jersey without an Interdistrict Choice participant, and that is due to the lack of capacity in suburban districts, not a lack of a desire to have the students and state money.

|

This excludes districts with populations under 1,000 because Essex Fells and Fairfield have had large percentage declines

but those declines are small in absolute size.

Source, NJ Enrollment Files

http://www.nj.gov/education/data/enr/ |

Would Consolidation Save Money? Tractenberg also endorses the "folk hypothesis" that governmental fragmentation is the cause of New Jersey's extreme property taxes.

Finally, we could once and for all confront New Jersey�s particularly virulent form of home rule. Consolidation of school districts and municipalities is routinely referred to as �a political third rail.� For three-quarters of a century this attitude has disabled us from addressing the gross inefficiencies -- fiscal, educational, social, and constitutional -- of our crazy quilt of undersized and colossally expensive municipalities and school districts. A former speaker of New Jersey�s Assembly, Alan Karcher, referred to it in a book title as Multiple Municipal Madness. As citizens and taxpayers, we excoriate politicians for our property taxes, by far the highest in the nation, but we cling with equal passion to our costly and dysfunctional governmental bodies.

It's a common belief that governmental fragmentation is the basic reason for New Jersey's high taxes, but it's based on a false premise that New Jersey has an inordinate number of localities. It is true NJ has a lot of localities per land area, but

in terms of localities per capita, New Jersey is average.In small districts and municipalities administrators tend to have multiple roles, so the ratio of students:administrators is the same as in larger towns.

Yes, New Jersey does spend more on central office administration than other states, but

we spend more on absolutely everything else too.

|

Source, US Census,

http://www.governing.com/gov-data/education-data/state-education-spending-per-pupil-data.html |

On the municipal level at least, there is

zero correlation between population size and government spending.

Where I do think consolidation could

eventually save money is if it caused changes in voting behavior.

Right now, many residents tolerate high school taxes because they know the money benefits their own children and they believe that higher school spending increases their own property values.

However, in a consolidated superdistrict, people would know that the money raised isn't directly benefiting their own kids and it would be illogical to believe that money spent countywide would disproportionately benefit one's own town and real estate values.

So, if consolidation into a countywide district made voters a lot more conservative with school taxes, then that would save money, but this isn't what Paul Tractenberg wants to happen.

Practical Problems Drive Political OppositionTractenberg chalks up opposition to consolidation to nameless "political bosses" and "wealthy suburbanites" who are motivated by racism, but opposition to municipal and school consolidations in New Jersey is more often motivated by pure sentimentalism.

Think of all the examples of demographically similar and adjacent towns refusing to consolidate municipal government.

- Scotch Plains and Fanwood already share a school district but have not even gotten to the referendum stage on effecting a municipal merger.

- Roxbury and Mount Arlington have not gotten to the referendum stage either, after seven years of study and advocacy.

- Sussex Boro and Wantage Township already share a school district and several other services, but have rejected a merger.

- South Orange and Maplewood already share a school district but have not been able to arrange a municipal merger. It is actually Maplewood, the slightly poorer town, that has spurned attempts at merging. When Maplewood had a vote on a merger commission the anti-merger slogan was "Keep Maplewood Maplewood."

Princeton is the exception that proves the rule, because voters there rejected consolidation three times (1953, 1979 and 1996) before narrowly approving it at the bottom of the Recession in 2011.

Where school district consolidations have occurred, like South Hunterdon, tax apportionment has been on a per student basis, a completely impractical idea for socioeconomically dissimilar towns in Essex like we are discussing here.

New Jersey's landscape of wealth and opportunity is very unequal and I wish that countywide districts had been created a century ago, but 100+ years of independent development of towns and school districts have created stark differences in taxation and school spending between towns and districts that would be very difficult to undo.

The Abbott decisions have, ironically, made consolidation even more complex since the Abbott decisions allowed distortions to occur in school and municipal spending. At this point, school tax rates have risen so much in non-Abbotts that if an Abbott and non-Abbott merged, the Abbott districts would end up paying higher taxes, meaning there would be strong opposition to consolidation even amongst the groups Tractenberg thinks would benefit the most.

Even if the tax problems, space problems, and transportation problems could be solved, I doubt any districts would want this because it is a loss of power over their own schools. Newark, which just got back local control over its schools, may be reluctant to give up that power again to a county it only has partial influence over?

Paul Tractenberg is right logically that consolidation follows from our noblest impulses and is suggested by

Brown v Board of Education, but the practical challenges of consolidation are too large to overcome. Even aside from political acquiescence (or judicial diktat), it would require some massive infusion of state municipal aid and transportation aid to be workable at all.

The elected officials (or "bosses," if they disagree with Tractenberg) who would oppose consolidation have some legitimate reasons for doing so.

-----

See Also:

What About Apportioning Taxes By Local Fair Share?

In theory, we could use an apportionment based on Local Fair Share in order to mitigate low income:property ratios in poorer towns, although this would actually not make much difference for most towns.

Newark has only 13.3% of Essex County's Local Fair Share, whereas it has 16.2% of Equalized Valuation, so Newark's tax increase would be smaller than under a pure Equalized Valuation apportionment, but the other Abbotts would pay basically the same amount.

Millburn's tax share would go from 11.47% of Equalized Valuation to 12.36% of Local Fair Share. Again, not a big difference.